Historic Highway US 101

Learn about two sections of US 101 that have historical significance.

Kalaloch Campground to Ruby Beach Segment - MP 157.7 to MP 164.5

Significance

The nearly seven-mile segment of US 101 from Mile Post (MP) 157.7 to MP 164.5 contains the last portion of the “Olympic Loop Highway” (formerly State Road 9, now US 101) built around the Olympic Peninsula. For that reason, the Kalaloch Campground to Ruby Beach segment is NRHP eligible per Criterion A. It is also NRHP eligible per Criterion C for the construction difficulties presented by topography, soils, extreme precipitation and the challenges of highway building in one of most remote corners of the US. The boundaries of the segment are identified by the highway mile posts between which integrity is retained in the roadway and its prism dimensions, limited sight distance due to curves and vertical obstructions and lack of clear zones normally present along major highways.

Background

Highway construction contractor Strong-Macdonald, Inc. of Tacoma built the 5.267-mile Browns Point to Cedar Creek section of State Road 9 (present US 101) in 1927-1931. After being awarded Contract No. 1158 on August 30, 1927, the contractor began shipping equipment and materials by “scow” from Tacoma. The Final Record Notes for Contract 1158 reported, “The project was located along the shoreline of the Pacific Ocean, in about the middle of the then uncompleted section of highway between Harlow Creek and Bogachiel river [sic], and was not accessible to ordinary means of transportation. The only practical avenue of approach was by the ocean and beach.”

The first batch of equipment, a gasoline-powered shovel, a Best 30 h.p. tractor, and a Fordson tractor, arrived at the mouth of the Hoh River on October 2, 1927, and was “moved along the beach” four miles to Cedar Creek. Construction began on October 20th with grubbing at Cedar Creek. The final Record Notes reported, “The transportation of supplies was one of the most serious problems confronting the contractor, as practically all of the hauling had to be done on the beach.” Hauling equipment on the beach proved difficult. The Best tractor’s attempts to pull a wheeled trailer proved “a total failure.” Supplies were then hauled on a sled until February 28, 1928, when the tractor was “lost in the surf.” Workers then carried supplies “by back-packing” until two tractors arrived overland in mid-April and resumed the hauling of supplies along the beach. Limited by tides and beach conditions tractors crawled through dynamited openings in rock outcrops, but high tides continued to flood vehicles: “On numerous occasions the motors were stalled by the surf and great difficulty was experienced in saving the equipment. In general, where materials could not be hauled directly to the site of the culvert under construction, they were hauled on the beach to the foot of the bluff near the site by tractor and trailer. They were then hoisted up the bluff by the Fordson donkey and carried to the set-up by car and track.”

Three more tractors arrived at the worksite in 1928, two in April “having come in over-land” and a third in early August. Presumably the vehicles came from the south, since construction of the highway to the north, the Nolan Creek to Cedar Creek section (Contract 1302, also by Strong & MacDonald), did not begin until June 1929, and the Nolan Creek and Hoh River bridges were not completed until 1931. The seven-mile Queets River to Browns Point (Contract 1136) section of State Highway 9 (US 101) to the south started construction in August 1927, but by spring of 1928 was in the early stages of construction. Although completion of the north end of that highway segment (Contract 1136) was delayed until the bridge over Kalaloch Creek was finished in August or September 1930, tractors may have been able to get through to the north.

During the nearly three years of construction for Contract 1158, the contractor built nine concrete box culverts and installed numerous concrete pipes under the new highway. When reduced drainage needs were determined for some drainages, four of the thirteen planned box culverts were replaced by concrete pipe installations, supplied by the E.W. Harrison Pipe Company of Tacoma. Cement was hauled in from the Olympic Portland Cement Company in Bellingham, while sand and gravels were obtained from beaches at the mouths of Minnie and Camp 4 creeks. Reinforcing steel was barged in from Northwest Steel Rolling Mills in Seattle. Severe weather usually stopped work between mid-October until late April each year. The engineer’s Final Record Notes remarked: “[A] great deal of trouble was encountered on account of slides from the fills, which were generally in rather narrow and deep ravines.”

Landslides and washouts of unstable fill material in and around previously installed culverts and graded roadway had to be stabilized with gravels from borrow sites. Workers shuffled machinery from one emergency to the next, often having to stop due to mechanical failure. At the site of the future culvert in the Steamboat Creek drainage, a plan and profile drawing mentions “Removing Log Jam.”

Between the start of work in October 1927 and completion of work in August 1931, the Department of Highways granted at least three contract extensions. Finally, by summer 1931, the only work remaining was to finish two road cuts and mine gravel from borrow sites to replace fill lost to slides and washouts. On August 18, 1931, after three years and ten months, work on the 5.267 miles of State Road 9 had been completed at a cost of $361,898.24 ($66,025.94 more than the contract amount of $295,872.30). The amount was a relatively small percentage of the roughly $10 million spent over more than a dozen years building the Olympic Loop Highway. The next week, on August 26-27, celebrations were held in Kalaloch to mark the opening of the 355-mile long (according to the Automobile Club of Washington, Seattle Daily Times, 9/1/1931, p. 3) Olympic Loop Highway, presently US 101. Governor Roland Hartley, BC Premier Simon F. Tolmie, Highway Department director Samuel Humes, and reportedly “several thousand others” were there, as well as members of the five coastal tribes: Quillayutes, Quinalts, Queets, Hoh and Makah.

Completion of the Kalaloch Campground to Ruby Beach segment of the highway realized the dream of connecting one of the most remote corners of the US via a road tied to Olympia and the Pacific Highway. Few other short sections of roadway had been so difficult to build and had such far-reaching effects, especially contrasted with the Cedar Creek to Nolan Creek section (Contract 1302, also with Strong & MacDonald) immediately to the north: “This contract [1302] did not show any unusual or difficult features. No new methods of construction or management was [sic] developed . . . the method of transportation and the kind of equipment required, had already been developed on Contract 1158 [i.e., most of the Kalaloch Campground to Ruby Beach section]. This section of the Olympic Highway, State Road No. 9, was perhaps the least difficult to construct of the entire Olympic Loop.” Addition of coastal lands to Olympic National Park in 1953 brought the Kalaloch Campground to Ruby Beach segment of US 101 under Park Service jurisdiction and probably contributed to the preservation of the original right-of-way.

Description

Beginning immediately north of the left-turn lane into the NPS Kalaloch Campground at MP 157.7 and proceeding north for nearly seven miles the roadway maintains the characteristics of a historic highway, i.e., narrow lanes and shoulders, limited sight distance due to curves and/or obstructions (roadway elevation gains) and trees within what would otherwise be a “clear zone” along a standard modern highway. Occasional pullouts and intersections with secondary roads diminish the feeling of the historic road driving experience only slightly. Roadway integrity continues to where the left-turn lane accessing Ruby Beach parking area begins at MP 164.5. That point marks the northern end of the 1927-31 construction done per Contract 1158 whose northern extent ended in the vicinity of Cedar Creek, which meets the Pacific Ocean at Ruby Beach. The southern end of construction per that contract is near Browns Point in the vicinity of MP 159.7, approximately two miles north of the southern end of the NRHP- eligible segment of US 101 Kalaloch Campground to Ruby Beach.

South end of the Kalaloch Campground to Ruby Beach segment of US 101 at MP 57.75.

Kalaloch Campground to Ruby Beach segment of US 101 adjacent to coastline at MP 158.35.

US 101 at Browns Point MP 159.76, near the south end of construction done under Contract 1158, Browns Point to Cedar Creek, 1927-1931.

North end of the Kalaloch Campground to Ruby Beach segment of US 101 at MP 164.52, near the north end of construction done under Contract 1158, Browns Point to Cedar Creek, 1927-1931.

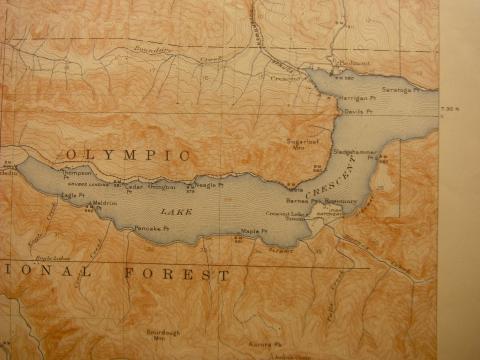

Lake Crescent Highway

US 101 MP 221 to MP 231.3

Significance

A 10.3-mile segment of US Highway 101, formerly known as the Olympic Loop Highway, along the southern shore of Lake Crescent was determined eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places per Criterion A as an early example of a Federal Aid Forest Road Project, a partnership involving federal agencies (the US Forest Service and Bureau of Public Roads) and the Washington State Highway Department in the early years of the national highway system. The segment is also NRHP eligible per Criterion C as a representation of early twentieth century highway engineering, design and construction methods in Washington state. The highway is largely intact and retains most of its character-defining features, as well as aspects of integrity essential for NRHP eligibility such as location, design, setting and feeling. Construction contracts, original as-built plans, historic photos and modern maps suggest the segment maintains all but approximately 0.9 mile (at Barnes Point) of its original alignment. Although some widening and removal of original timber retaining walls and culverts has occurred, the present roadway dimensions coincide with profile and prism engineering drawings of the segment dating to 1949 and earlier.

Background

Until just after the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, Lake Crescent remained inaccessible by automobile. In 1912, Clallam County commissioners funded construction of a ferry to haul cars across the lake. Motorists could then drive from Port Angeles to East Beach, catch a ferry to Fairholm and drive west as far as Beaver. Department of Highways “State day labor” forces began work June 1, 1921, and completed work May 1, 1922, on a 10.8-mile segment of highway from Fairholm to East Beach. Sited within what was then the Olympic National Forest, the segment met the requirements of Federal Forest Road Projects which were administered jointly by the US Forest Service and the Bureau of Public Roads. When completed, the so-called Crescent Lake Highway provided the first direct road connection between the east and west ends of Clallam County. It became a segment of US Highway 101 and part of the 365-mile-long Olympic Loop Highway when Governor Roland Hartley officially opened Primary State Highway 9 on August 26, 1931. At that time Crescent Lake was within the boundaries of the Olympic National Forest, established in 1897. On June 29, 1938, the Olympic National Park was established, bringing the lake and portions of US 101 (including the segment of highway along Lake Crescent) within the jurisdiction of the National Park Service. In 1949, Hugh Govan widened that segment of highway, built a retaining wall on a steep slope above the highway and completed other improvements of the highway along the south shore of Lake. In conjunction with Govan’s work, the Port Construction Company of Port Angeles built the Lake Crescent Half Bridges numbers 101/326 & 101/327 at Storm King Point. To diminish rock fall onto the roadway, the bridge construction contract included installation of wire mesh attached to steel strands secured on 13 trees atop the cliff above Bridge 101/326. A debris slide caused by heavy snow and rainfall closed the highway in this vicinity in February 1923.

Description

The 10.3-mile highway segment of US 101 follows the southern shoreline of Lake Crescent from Mile Post 221 near Fairholm at the southwest end of the lake to a point where the roadway diverges from the southeast shoreline at MP 231.3. It is characterized by narrow 10- to 11-foot-wide lanes, shoulders that vary from nonexistent to 12-inches in width, limited sight distance and minimal clear zones.

Upgrades and improvements to the Lake Crescent Highway have continued to the present day, reflecting a subtle evolution beginning shortly after its completion in 1921. Minor upgrades to the roadway and its features were necessary for the segment to continue functioning as a modern highway, particularly as traffic volumes increased. The cumulative effects of multiple decades of modifications have slightly changed the road’s profile. However, a majority of upgrades are over fifty years in age and are considered elements contributing to the highway’s significance, including the Lake Crescent Half Bridges numbers 101/326 & 101/327 at Storm King Point (1949).

Newly constructed Lake Crescent Highway along the south shore of Lake Crescent, as shown in 1922, prior to re-routed 0.9-mile segment at Barnes Point (1949)

Lake Crescent Highway ca. 1920s.

Lake Crescent Highway, ca. 1927, and bridge.

Present US 101 (historic Lake Crescent Highway) crossing Half-Bridge #101/326.

Lake Crescent Half-Bridge #101/326, 2014.

Slow down – lives are on the line.

In 2023, speeding continued to be a top reason for work zone crashes.

Even one life lost is too many.

Fatal work zone crashes doubled in 2023 - Washington had 10 fatal work zone crashes on state roads.

It's in EVERYONE’S best interest.

95% of people hurt in work zones are drivers, their passengers or passing pedestrians, not just our road crews.